How Did the Us Supreme Court Acquire the Power of Judicial Review?

On Feb 24, 1803, Chief Justice John Marshall issued the Supreme Court's decision in Marbury 5. Madison, establishing the ramble and philosophical principles behind the high court'south power of judicial review.

The dramatic tale begins with the presidential election of 1800, in which President John Adams, a Federalist, lost reelection to Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican. Congress also inverse hands, with the Democratic-Republicans achieving majorities in both chambers.

The dramatic tale begins with the presidential election of 1800, in which President John Adams, a Federalist, lost reelection to Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican. Congress also inverse hands, with the Democratic-Republicans achieving majorities in both chambers.

Adams and the Federalists could see the writing on the wall: the political party'south power had been limited to the judicial branch. In a bid to strengthen Federalist power, President Adams appointed Secretary of State John Marshall to be Main Justice of the United states. The Federalists, with weeks remaining in the lame-duck session, passed a new Judiciary Deed—the "Circuit Court Act"—which expanded the jurisdiction of the circuit courts and created six new circuits with 16 new judicial seats. (The law also eliminated circuit duty for Supreme Courtroom justices, and provided for easier removal of litigation from state to federal courtroom.)

To fill the newly expanded judiciary, on March one, 1801, three days earlier Jefferson's inauguration, Adams stayed upwardly late into the night signing commissions for the new judges, including the 42 new Justices of the Peace. The "midnight appointments," as they came to be known, were as well notarized by Marshall, still performing his secretarial duties. Just the blitz of presidential transition led to the assistants's failure to deliver several of those commissions, including that owed to William Marbury, who had been named a justice of the peace for the District of Columbia. On March four, upon bold the office of the presidency, Jefferson ordered Secretarial assistant of State James Madison not to deliver the commissions.

Marbury's lost commission became a exam instance for the ousted Federalists who were outraged over the Autonomous-Republican Congress'southward repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801 and the passing of a replacement deed in 1802, and who were hoping to test its constitutionality as before long every bit possible. Before the Supreme Court considered the example in Feb, Congress held a viciously partisan debate over the constitutionality of the Repeal Act, with Republicans claiming that the people were the concluding judges of the constitutionality of acts of Congress. Marbury, with representation from Adams' Attorney General Charles Lee, demanded a writ of mandamus from the Supreme Court to obtain his commission.

In Grand arbury v. Madison, the Court was asked to answer iii questions. Did Marbury have a right to his commission? If he had such a right, and the right was violated, did the police force provide a remedy? And if the law provided a remedy, was the proper remedy a directly order from the Supreme Court?

Writing for the Courtroom in 1803, Marshall answered the first two questions resoundingly in the affirmative. Marbury'due south committee had been signed past the President and sealed by the Secretarial assistant of Country, he noted, establishing an appointment that could not be revoked by a new executive. Failure to deliver the commission thus violated Marbury's legal right to the office.

Marshall also ruled that Marbury was indeed entitled to a legal remedy for his injury. Citing the dandy William Blackstone's Commentaries, the Principal Justice declared "a general and indisputable rule" that, where a legal right is established, a legal remedy exists for a violation of that right.

It was in the 3rd office of the stance that presented a dilemma: If Marshall decided to grant the remedy and order commitment of the commissions, he risked only existence ignored by his rivals, thereby exposing the young Supreme Court equally powerless to enforce its decisions, and dissentious its future legitimacy. Simply siding with Madison would have been seen as caving to political pressure—an equally damaging effect, peculiarly to Marshall who valued the Court as a nonpartisan institution. The ultimate resolution is seen by many scholars as a fine balancing of these interests: Marshall ruled that the Supreme Court could not society delivery of the commissions, because the law establishing such a ability was unconstitutional itself.

That law, Section xiii of the Judiciary Deed of 1789, said the Court had "original jurisdiction" in a instance like Marbury—in other words, Marbury was able to bring his lawsuit direct to the Supreme Court instead of first going through lower courts. Citing Article III, Department 2 of the Constitution, Marshall pointed out that the Supreme Court was given original jurisdiction only in cases "affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls" or in cases "in which a Country shall be Party." Had the Founders intended to empower Congress to assign original jurisdiction, Marshall reasoned, they would not take enumerated those types of cases. Congress, therefore, was exerting ability information technology did not have.

This was an exercise of judicial review, the power to review the constitutionality of legislation. To exist sure, Marshall did not invent judicial review—several land courts had already exercised judicial review, and delegates to the Constitutional Convention and ratifying debates spoke explicitly most such power existence given to the federal courts. The Court itself in the 1796 instance of Hylton v. United States reviewed and upheld an act of Congress as constitutional—with Alexander Hamilton arguing for the validity of the taxation in question. And in Ware v. Hylton, the Supreme Court struck down a Virginia creditor law in disharmonize with the Treaty of Paris based on federal supremacy.

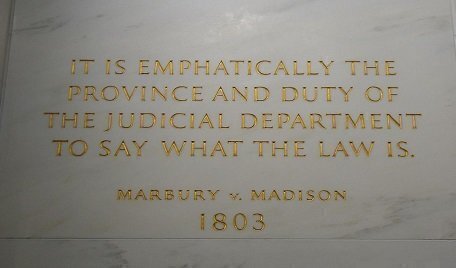

Still, the legendary Chief Justice applied judicial review firmly and artfully to the nation's highest court. "It is emphatically the duty of the Judicial Section," he wrote, "to say what the constabulary is." Until Marbury, judicial review was not widely accustomed in cases of doubtful unconstitutionality and was not an aspect of ordinary judicial action, and its telescopic was more modest. And while Marbury was not a particularly controversial decision in 1803, it has remained the source of scholarly debate.

In the short run, Jefferson and the Autonomous-Republicans got what they wanted: Marbury and the other "midnight appointments" were denied commissions. Only in the long run, Marshall got what he wanted: A independent Supreme Court with the power of judicial review. As historian Gordon Wood eloquently put information technology, Marshall's greatest achievement was not invented judicial review, merely "maintaining the Court's being and asserting its independence in a hostile Republican climate."

For more than reading on the debate betwixt scholars over the meaning of Marbury and its implication for judicial review and judicial supremacy, consider the following:

Bruce Ackerman, Failure of the Founding Fathers: Jefferson, Marshall, and the Rise of Presidential Democracy (Harvard University Press 2005)

Albert Beveridge, The Life of John Marshall (1919)

Edward S. Corwin, John Marshall and the Constitution: A Chronicle of the Supreme Court (1977)

Mark A. Graber, "Passive-Aggressive Virtues: Cohens 5. Virginia and the Problematic Establishment of Judicial Ability," 12 Const. Comm. 68, https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/167160/12_01_Graber.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Charles Hobson, The Groovy Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Rule of Law (1996)

Michael J. Klarman, "How Great Were the 'Bang-up' Marshall Court Decisions?" Va. L. Rev. (2001), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=270081

Larry Kramer, "Marbury and the Retreat from Judicial Supremacy," 20 Const. Comm. 205 (2003), https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/183156/20_02_Kramer.pdf

Leonard W. Levy, Original Intent and the Framers Constitution (2000)

Jed Handelsman Shugerman, "Marbury and Judicial Deference: The Shadow of Whittington 5. Polk and Maryland Judiciary Boxing," v U. Pa. J. Const. L. 58 (2002), https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/jcl/vol5/iss1/three/

William W. Van Alstyne, "A Disquisitional Guide to Marbury v. Madison, 18 Duke L. J. 1-47 (1969), https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/faculty_scholarship/544/

Louise Weinberg, "Marbury v. Madison: A Bicentennial Symposium," 89 Va. L. Rev. 1235 (2003), https://police force.utexas.edu/kinesthesia/uploads/publication_files/ourmarburypub.pdf

Nicholas Mosvick is a Senior Fellow for Constitutional Content at the National Constitution Center.

easterlingforer1944.blogspot.com

Source: https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/marbury-v-madison-and-the-independent-supreme-court

0 Response to "How Did the Us Supreme Court Acquire the Power of Judicial Review?"

Post a Comment